Opinions expressed by Entrepreneur contributors are their own.

You’re reading Entrepreneur Middle East, an international franchise of Entrepreneur Media.

Egypt has always been a dominant breeding ground for startups in the region, whether you look at the size of the ecosystem, the amount of venture capital deals it attracts, or the overall amount of funding the startups within the ecosystem attract compared to others in the region.

Egypt also plays in two distinct geographies: it’s a major player in the larger Africa ecosystem, and it is also a dominant player in the MENA region.

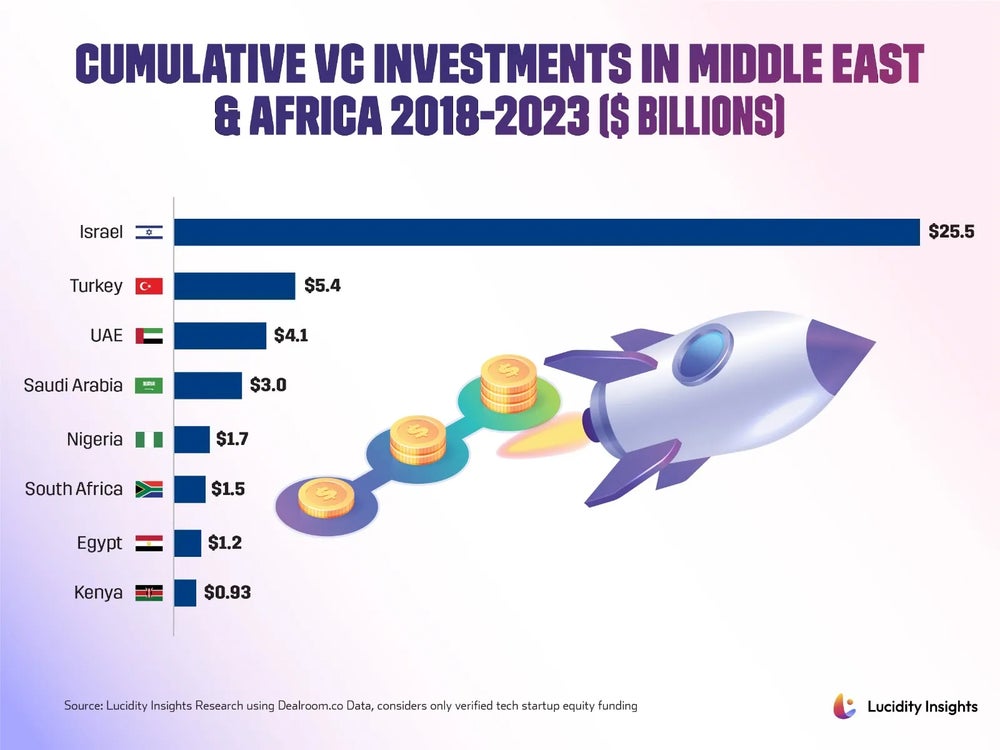

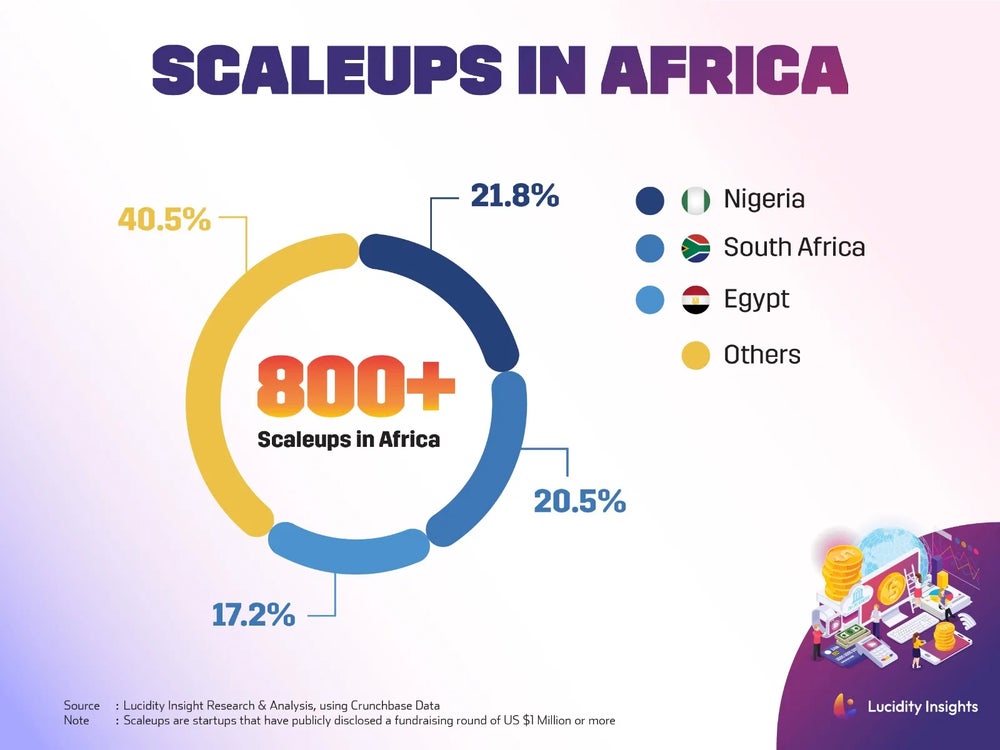

In Africa, the big four markets for tech ecosystems are consistently Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt, closely followed by Kenya. In the MENA region, the rankings are Israel out front, United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia, followed by Egypt. Of course, if you include Turkey, then Egypt moves to fifth place.

Whichever metric you use, whether it’s startup funding raised, or the number of scaleups in each ecosystem (which are defined as startups that have raised US$1 million or more), the results are largely the same. All in all, the point is that Egypt is a major player across regions.

Egypt has also benefited from global macroeconomic conditions that seemed to funnel liquidity into emerging markets, at a rate never seen before. Lucidity Insights spoke with Kareem Aziz, who leads the International Financial Centre Corporation’s (IFC) investments into digital payments startups around the world, and has been investing in startups on behalf of the entity for the past 20 years.

“Venture capital (VC) had an incredible journey in the last five years, globally,” Aziz says. “There was an extraordinary amount of liquidity, mostly driven by the US, but also coming from many developed markets like the European Union (EU) and Asia. It catalyzed venture funding in emerging markets, and it particularly benefitted markets with large populations like Egypt, Nigeria, and Pakistan.”

Related: 10 Graphs You Need To See To Understand Egypt’s Startup Ecosystem

Source: Lucidity Insights

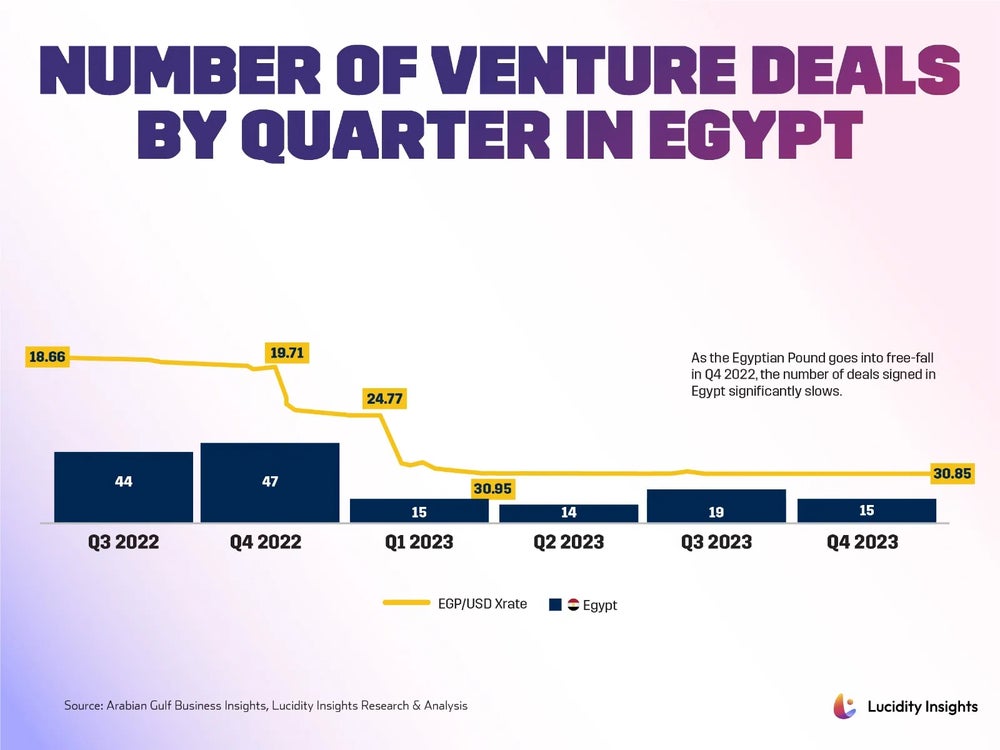

As the VC winter well and truly set in around the globe in 2023, it is clear that the money that came into Egypt during the global investor bull-run was a catalytic force, but maturation still needs to happen across the entire ecosystem. Egypt was signing approximately 45 deals per quarter in 2022, and in 2023, that number dramatically reduced to approximately 15 deals per quarter. In Egypt, just like in markets around the world—but especially in markets with currency risk like Nigeria and Pakistan—as money dried up, undisciplined investors and their startups have hit hard times, and have had to take a close look at themselves in the mirror.

Tarek Assaad, Founding Partner at Algebra Ventures, says, “When capital was easier to come by, many startups threw money at marketing for user acquisition after fundraising. Of course, revenues went up, but it was an unsustainable model. Those companies are really hurting right now. In contrast, more disciplined startups that invested in technology tended to grow slower, but have retained customers and stronger balance sheets.”

Source: Lucidity Insights

The path to rectifying undisciplined balance sheets and spending really leaves two broad options to survive: either cut back on costs, or expand revenue. Cutting costs can be a painful exercise, and so most opt to try and expand revenues first wherever possible. In reality, both exercises are required simultaneously.

When it comes to Egyptian startups expanding revenues or cash flow, there are a few avenues that can be taken

1. Fundraising Strong incumbents in their sector could raise some capital to consolidate their market leadership position, but newbies were less likely to get funded. Due to the global cost of capital increasing as interest rates rise, fundraising in this climate is not impossible, but difficult. It is even more difficult for those startups that don’t have a healthy track record of disciplined cash management. If you were a startup that was burning through fundraising to grow your company, assuming that you could simply fundraise again when the money ran out, you were in for a rude awakening.

Source: Lucidity Insights

2. Increasing Prices For any startup, increasing prices of products that already have been in the market is a difficult task, especially when you have loyal customers that have been paying a set price for what they have been receiving. Perhaps you could charge new customers a different higher price, but the truth is that in a market like Egypt, where inflation has been running rampant, and everyday citizens have been feeling a pinch on their wallets, increasing pricing runs the risk of losing customers and revenues, while likely not being a gamechanging enough tactic.

Source: Lucidity Insights

3. Expanding Your Consumer Base Then we ask ourselves, how can we increase our consumer base, without overspending on customer acquisition? This is the question that many startups have been asking themselves to not only survive these times, but to figure out a way back to thriving during these times. Attempting to acquire customers in Egypt in the current climate where customers don’t have as much disposable income as a year prior makes for a challenging environment. This is where Egyptian startups have started to think about expanding their offerings to customers outside of the country.

Ultimately, for startups that cannot expand geographically and have an Egypt-only business, the only prescription is survival mode for now. Cut costs, provide exceptional service, survive and hope for the macroeconomic tides to turn. Bassem Raafat, Principal at A15, reiterated this, saying, “Hyperlocal, operationally intensive, and/or heavily regulated businesses that cannot easily expand geographically will likely face a tougher time attracting capital in the current environment.”

A question remains for those startups that have the option to bring their services to other markets. And that simply is: “Where should we expand to?” This is where a debate begins. Are Egyptian startups better suited to serve other African markets, or the rest of the Middle East? The answer is not so straightforward.

Source: Lucidity Insights

EGYPT: SPRINGBOARD TO AFRICA OR THE MIDDLE EAST?

Historically, when Egyptian startups considered geographical expansion beyond its borders, they tended to grow towards the Middle East instead of Africa. This was mostly due to a perceived ease of doing business; Egyptian entrepreneurs often think the rest of the Middle East is an easier market to crack, because of cultural similarities and the shared Arabic language.

In addition, there is a perception that Dubai and Riyadh are home to a “pot of gold” at the end of the rainbow. This “pot of gold” references both easier access to capital for fundraising, as well as access to a wealthier consumer base in the GCC that have a propensity to pay more for the same product. In essence, Egyptian startups could sell roughly the same product they were selling in Egypt in Saudi Arabia or the United Arab Emirates for significantly higher multiples. But that story, many investors say, is only half of a very old story.

The logic used to go, if Egyptian startups could produce technologically advanced solutions in Egypt for a fraction of the cost that GCC startups could produce it, Egyptian startups could win in these markets, and this was the case, for some time. But today, many Dubai-based or Riyadh-based startups have their own development teams working in low-cost markets like Egypt, Lebanon, South East Asia, or even other African and some European markets. In that light, Egyptian startups may fare better, bringing their tech solutions to countries that not only need it, but have less competition in Africa.

Source: Lucidity Insights

As we speak to many investors, they say that Egyptian startups need to consider the rest of Africa for a variety of reasons, and that they should dig a little bit deeper beyond the short-term incentives on offer in Gulf markets, today. “Egypt should be a hub and entry point for the rest of Africa,” IFC’s Aziz points out. “Unfortunately, what is happening is that Egyptians are somewhat inwardly-focused, and not outwardly-focused. Frankly, many of them think, ‘Why go to the rest of Africa? I’m happy here.’ That mentality needs to change.” Aziz reiterates that this mentality shift needs to come from both local startup founders as well as local investors. “Egyptian VC should be developing relationships in other African markets where Egyptian founders want to expand to,” he adds,

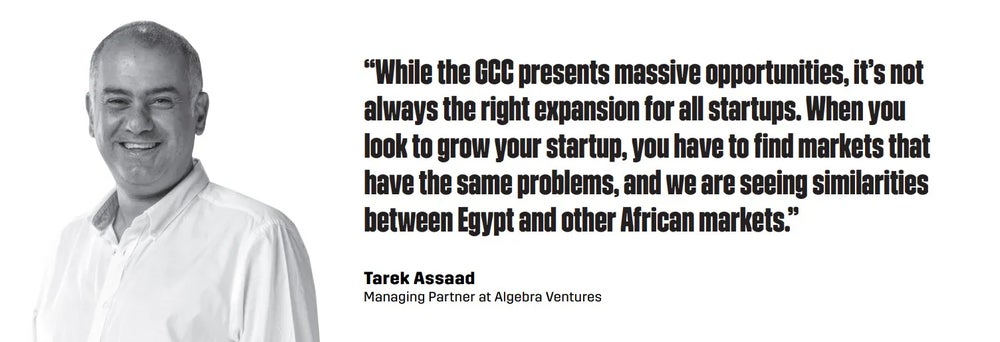

Algebra Ventures’ Assaad also echoed that Egyptian startups that build a strong product in Egypt are more likely to do better in Africa. “Today, the issues that our tech companies are working to solve are issues like access to credit, access to data and information, and financial inclusion in a market where less than 5% of Egyptians own a credit card. These are the same fundamental issues that other African markets are facing. While the GCC presents massive opportunities, it’s not always the right expansion for all startups. When you look to grow your startup, you have to find markets that have the same problems, and we are seeing similarities between Egypt and other African markets.”

Assaad also tells us that there is an increasing number of exits where Egyptian startups are getting acquired by other African startups. “Algebra Ventures has had two such exits, where our Egyptian portfolio companies were bought-up by a Nigerian company, and another by a South African startup,” he shares. That said, there is no standard template; the decision as to which market to expand into entirely depends on the startup, the problem they are trying to solve for, and the sector that they are in. “Some fintechs often don’t particularly travel well,” Aziz notes. “Lending, for example, requires you to be hyper-localized, and because of local market regulations, licensing issues, and a plethora of ever-changing market dynamics in each market, it is rarely a plug-and-play scenario. It doesn’t scale easily, when you have to customize your offering to very specific customer profiles.”

There is also an array of factors to consider beyond access to capital and operating language that is on offer in the GCC markets. Basic things such as the fact that the GCC is a predominantly iOS market, while Egypt and the rest of Africa is an Android market, also impacts players. Plus, the access to capital may improve in the Gulf, but the cost of expanding and operating in the GCC is significantly higher than expanding and operating in Africa. The competitive landscape and the startup’s unique selling point changes as well, depending on where it chooses to go.

One thing investors are starting to agree on is that Africa can no longer be ignored. There are many markets in Africa that are looking increasingly attractive for Egyptian startups to not only compete in, but where Egyptian startups may have the competitive edge. Egyptian entrepreneurs are often considered resilient and industrious, but how many can say that they have a pan-Africa vision?

Sawari Ventures is one such player. Ahmed El Alfi, Founding Partner at Sawari Ventures, told us that he is convinced of the massive potential for innovation and impact in Africa, but despite similarities in demographics and addressable challenges, startups seem to be struggling to scale across the continent. “We believe this is not only due to a funding gap, but because there aren’t enough regional, pan-African investors with the network, capital, and ability to bridge existing gaps and support startups with regional aspirations,” El Alfi says. He also comments that while there have been more and more pan-African funds launched in recent years, none are operating out of Egypt- one of the continent’s top three startup ecosystems. He goes on to say he is fundraising for just such a fund in 2024. “We are looking forward to step into this gap,” he says. Inevitably, others will follow.

For more insights on Egypt’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, check out the report, Investing in Egypt’s Startup Ecosystem, here.

This article was originally published on Lucidity Insights, a partner of Entrepreneur Middle East in developing special reports on the Middle East and Africa’s tech and entrepreneurial ecosystems.