Advisors and lawyers now have clients in the era of private equity and venture capital “big money” divorces. The quirks of the ways in which these asset classes work have particular implications for settlements, as this article shows.

The following article is illustrates the complexities arising

from divorce settlements when one or both of the parties is

involved in the areas of venture capital and private equity.

These areas are changing: the new Labour government in the UK

wants to tax “carried interest” differently

from hitherto – which could affect the earnings of

those involved. Even so, recent cases highlight why the VC and PE

sectors create particularl issues for those going through

divorces.

The authors are Joshua Moger, partner, Family Law and

Catherine Costley, partner, Funds, Finance and Regulatory at

law firm Fladgate.

Ella Leonard

Joshua Moger

The editors are pleased to share these insights; the usual

disclaimers apply. Email tom.burroughes@wealthbriefing.com

if you wish to respond.

“Big money” divorces move with the financial cycles. Pre-2000

they were the landed gentry. From 2000 to 2008 it was the

bankers. From 2008 to 2020 it was the turn of entrepreneurs whose

businesses had grown exponentially post-financial

crash.

We are now in a new era – the private equity (PE) and venture

capital (VC) “big money” divorces. The UK now has the second

largest private equity market in Europe, relative to GDP. The UK

PE industry has more than doubled from £1.8 trillion ($2.33

trillion) in 2012, to £3.6 trillion in 2023 (1). But it is the PE

remuneration structures that make PE divorces unique, and why

having advice not only from a matrimonial lawyer, but a funds

lawyer too, is of fundamental importance. Bankers have

traditionally received bonuses annually – but carry entitlement

is awarded up front, with frequently decade long horizons for

payout – what happens if a divorce takes place mid-way through

the fund life?

Arguably co-invest rewards should be treated differently; it is

often funded by the PE professional putting matrimonial funds in

– but do judges appreciate that distinction?

However, this new era is “young.” Despite numerous PE

divorces coming across our desks, there is only really one

precedent setting case law – A v M [2021] and that case was

decided at first instance, i.e. it is not an appeal decision and

therefore does not bind other judges. It also related to a small

PE house co-owned by the husband and his business partner, which

is not the norm for the PE industry.

This means for PE professionals divorcing (and those thinking of

pre-nuptial or mid-nuptial agreements), that whilst A v M is very

helpful guidance, there is plenty of scope for lawyers to

distinguish it from the PE cases on their desk – to seek to

reshape the A v M guidance to achieve a better outcome for their

clients.

A v M

In 2016 the husband was awarded carry and co-invest in “Fund

1.” In 2018, it was awarded to him in “Fund 2.” The

wife petitioned for divorce in 2019 and the final hearing was in

October 2021. The end of the two fund terms (if not extended)

would be between 2025 to 2028. This gap between award, vesting

and payout is entirely standard which means that this situation

is not uncommon in PE divorces.

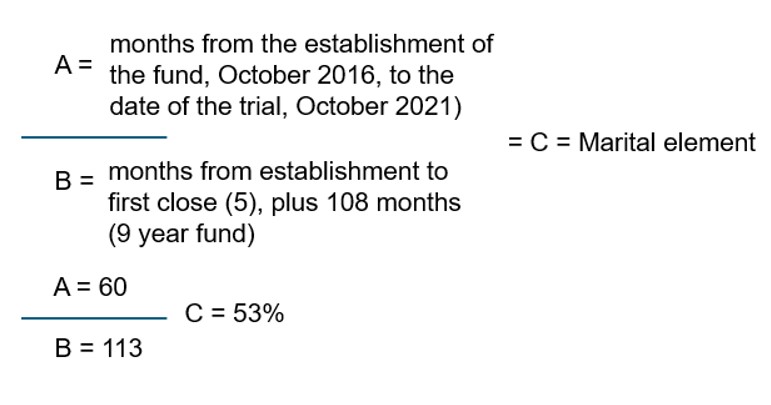

Mr Justice Mostyn (“Mostyn J”) alighted upon a linear,

time-based, formula to determine the ‘marital’ element of the

husband’s carry, which would be shared equally. Fund 1 was

established in October 2016 (first close March 2017) with

committed funds of €187 million ($203.7 million). Fund 2 was

established in October 2018 (first close June 2019) with

committed funds of €323 million. The funds had slightly different

anticipated terms and extension periods, however Mostyn J used an

assumed term of nine years from the first close for both. His

formula to determine the ‘marital’ element, as applied to Fund 1,

was:

Therefore 53 per cent of the carry in Fund 1 was marital (the

wife would receive 26.5 per cent). The same calculation for Fund

2 produced 31 per cent as marital (the wife receiving 15.5 per

cent). However, determining that the husband “would be much less

unhappy if [the wife] were a shadow carry partner in one fund

only” the judge “relocate[d] the wife’s share of the husband’s

carry in Fund 2 in the husband’s carry in Fund 1.

Mostyn J factored in that the Fund 2 committed funds (and

therefore potential carry value) were far larger than the Fund 1

size, meaning that this reattribution gave the wife a 48.53 per

cent interest in the carry payout from Fund 1, and no entitlement

from Fund 2. No account was taken of the relative performance of

the two funds and the potential effect of treating the

entitlement in this way. The wife’s entitlement was tied to the

husband’s carry, i.e. as and when the husband received carry

payouts, 48.53 per cent of that (net) would be transferred to the

wife.

Comparatively Mostyn J shared the co-invest “equally.” He

gave no reasoning for this different treatment of

co-invest.

Possible alternative approaches

As above, A v M is the only recent PE divorce precedent. There

remains scope for a different judge to take another

approach:

1. In A v M the husband effectively started his own PE fund

but most people working in PE are employees/partners in a large

PE house. Another judge may say the post-divorce effort (and

risk) in those circumstances is lesser than in A v M and discount

the amount of ‘post-matrimonial credit’ in calculating the

marital element.

2. Another judge may be willing to distinguish between carry

payout on a European waterfall structure (aggregate/end of the

fund life) and that on a US waterfall structure (deal-by-deal).

They may also factor in the impact of clawback clauses.

3. It is arguable that the “harvest” phase of a PE

fund, typically towards the end, is where most endeavour, risk

and skill is at play. If the parties separated or divorced

shortly before the harvesting phase, a different judge may take

greater account of this ‘enhanced’ post-separation endeavour,

rather than treating it linearly with the other phases.

4. Mostyn J shared the co-invest equally. There was no

reasoning given. It is assumed that it was because the

co-investment was made with marital funds. However, another judge

may say that this unduly disregards the husband’s post-separation

endeavour for the co-invest to payout or alternatively that the

post-separation endeavour is adequately rewarded in his share of

the carry.

5. Mostyn J used a marital period ending with the date of

the trial, rather than the date of the divorce petition. If that

date (July 2019) had been used, the marital element of Fund 1

would have been 29 per cent (compared with 53 per cent).

Another judge may use the date of divorce petition or date of

separation.

6. The use of the “establishment of the fund” start date

might not be followed. Another judge may use an earlier relevant

date, to reflect the preparatory work prior to establishing a

fund. Or they may simply use the ‘first close’ date for A (in the

calculation), taking the view that this is when the real effort,

and investment, starts.

7. Mostyn J’s view was that carry is a “hybrid resource”

with characteristics of income and capital. In dividing the

carry in the way he did, the judge effectively treated it as

capital. This capital/income distinction is crucial as it is well

established law that applicants can share capital accrued during

the marriage but have no right to share income. A different judge

may treat it as income.

8. If Fund 1 didn’t meet the hurdle by 2026, and Fund 2 did,

Mostyn J’s approach of aggregating the wife’s interest into Fund

1 would mean that she receives a nil payout from her 48.53 per

cent interest, and the husband retains his Fund 2 payout in full.

Another judge might say that is too high a risk of occurring, and

not aggregate in the way Mostyn J did.

9. A v M does not address the situation where one party

seeks to be ‘cashed out’ of the share that they would otherwise

have in the other’s carry. Cashing out is arguably even more

fraught with issues, particularly relating to valuation, but

other judges may be amenable to it in the right

circumstances.

In this “new era” of PE divorces, A v M is a helpful first

precedent. But precedent setting cases ‘two’ and ‘three’ may be

even more important. As will be getting the right matrimonial and

funds advice.

Footnote

1, Statista, June 2024