The trucking industry is showing signs of recovery after a prolonged downturn, but potential tariffs on Chinese, Mexican, and Canadian goods could threaten economic stability and further increase costs for fleets, according to Bob Costello, chief economist at the American Trucking Associations (ATA).

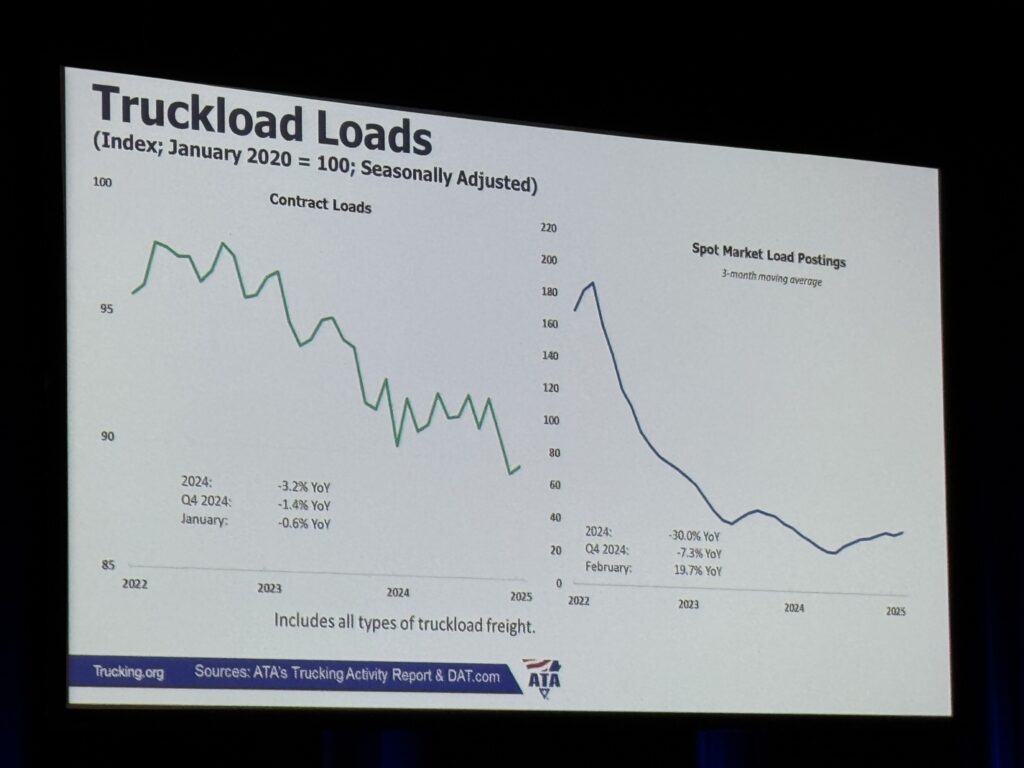

Speaking at the Truckload Carriers Association’s (TCA) annual convention in Phoenix, Ari., Costello said that the past two years have been especially difficult for the trucking sector, with contract freight volumes down 3.2% and spot market loads plunging by 30% year over year in 2024.

The freight recession lasted 27 months — longer than the 11-month Great Recession downturn in 2008-09 — but with a shallower total decline of 8.8% compared to the 23.8% drop seen during the financial crisis.

“That is just a slow, slow tearing off of the band-aid, and why it felt so bad,” Costello said.

The outlook, however, is improving. After a post-pandemic surge in travel and services spending, consumer spending patterns are finally shifting back toward goods. Goods purchases are projected to grow by 3.3% in 2025 and 2.6% in 2026, while service spending is expected to rise by about 2% this year.

“Retail inventories in particular, are quite low, but even wholesaler inventories are at a good place. Manufacturing is a little elevated but getting better. So, all of this because this was a major headwind on freight volumes for the last couple of years. Because why order more goods when I already have them in inventory?” Costello added. “So we’ve gone from a headwind to maybe not a tailwind, but potentially a little tailwind.”

Recovery indicators

While the freight downturn has been particularly harsh on the spot market, there are early signs of stabilization in contract freight.

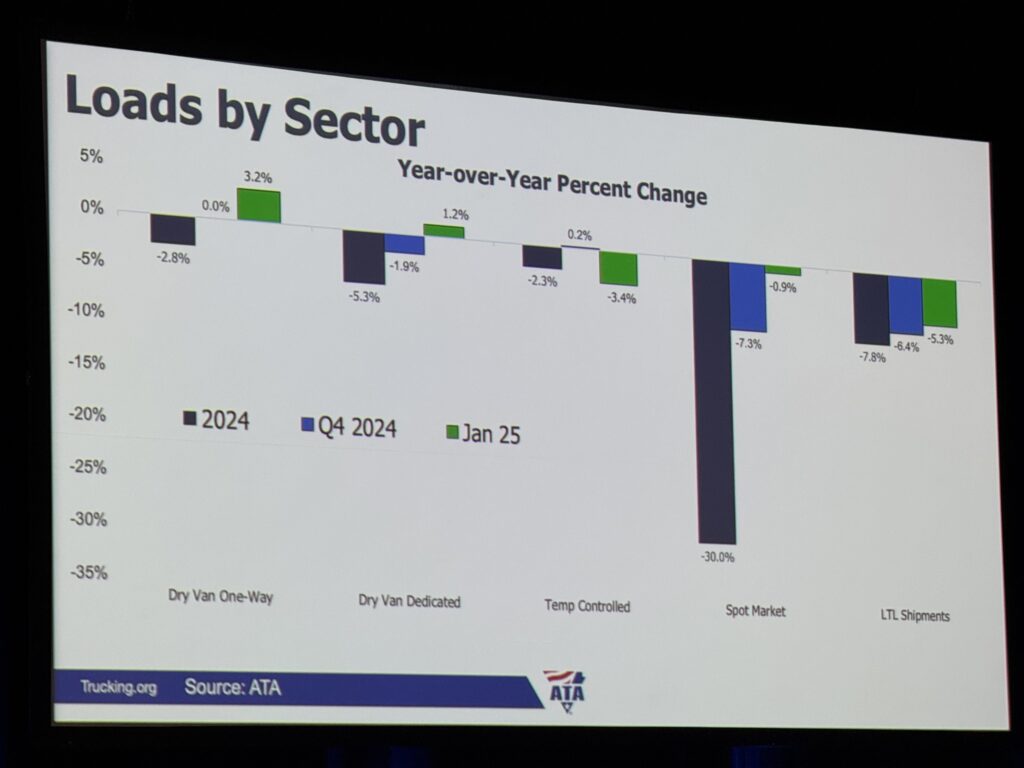

Even despite spot market loads seeing a 30% decline in 2024, ATA data shows a slight improvement by early 2025 (-7.3% in Q4, and -0.9% in January 2025).

Meanwhile, dry van freight — both one-way and dedicated — has started to level out. Dry van one-way loads, which fell 2.8% in 2024, flattened by Q4 and ticked up 3.2% in January. Dry van dedicated freight, which dropped 5.3% last year, also rebounded slightly.

Less-than-truckload (LTL) volumes fell 7.8% in 2024 but have since moderated, and temperature-controlled freight was beginning to stabilize in Q4 2024 but fell by 3% in early 2025.

Other economic indicators also point to an improving freight market. Factory production is rising, wholesale levels are continuing to rise, and housing and construction activity is projected to help generate freight demand, too.

However, the recovery won’t be the same across all trucking segments. Flatbed freight remains one of the stronger performers, with Castello calling it one of the better sectors in the truckload space. Meanwhile, for-hire carriers continue to struggle as private fleets expand and handle more of their own freight.

But it has not been easy on private fleets either — while they expanded during the pandemic-driven freight boom, that growth is now straining their ability to operate efficiently.

“I think it was a knee-jerk reaction by a lot of private fleets. I don’t think that’s where they want to be. I don’t think they want to have more trucks, because now they start to have some of the problems that all of you [for-hire carriers] face,” Costello explained, referring to high operating costs, driver shortages, and excess equipment.

This could push more freight back to for-hire carriers, though it would take time.

“We’re in a better place than we were a year ago, but that doesn’t mean we’re in the clear,” he summed up. “There are still plenty of risks out there.”

Tariffs

Tariffs are among those risks — a 25% tariff on goods from Canada and Mexico could increase the cost of new tractors by more than US$35,000 per vehicle, hitting carriers that rely on trucks assembled in Mexico. The Trump administration has also proposed an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports and a 25% tariff on steel and aluminum.

“If [tariffs] are in for any substantial amount of time, I think that brings in a real risk of macro-recession, no doubt about it,” he said, “It’s going to be a drag on freight volumes, because tariffs, after all, are taxes. As importers pay those, they’ve got to raise prices. When you raise prices on goods, people are going to buy less of them.”

Costello also highlighted the risk of retaliatory tariffs, which could further disrupt supply chains and reduce freight demand.

Another concern is a proposed vessel port call fee, which, if goes into effect, would charge $1 million to $3 million per shipment for China-based vessels. If implemented, this policy could seriously change freight flows at U.S. ports as importers shift goods to alternative entry points to avoid higher costs.

“Capacity has been leaving the industry. [Fleets] did not feel it because demand wasn’t really good.”

Bob Costello

Even as demand slowly returns to the market, capacity continues to shrink.

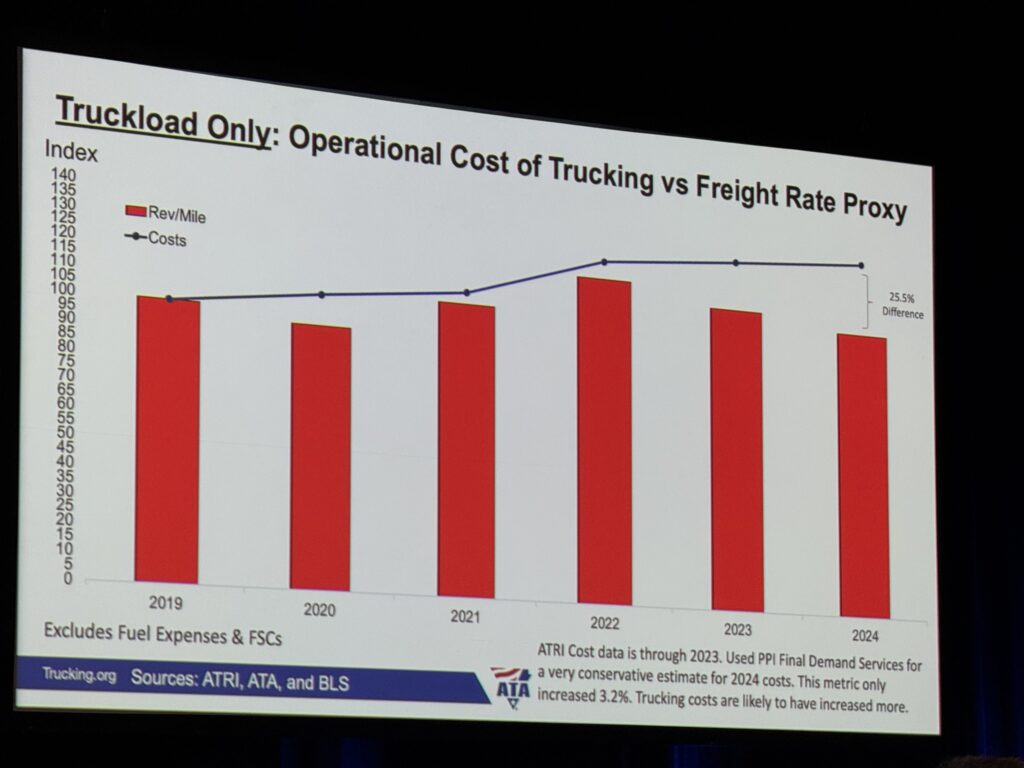

Cost pressures remain a challenge, especially with driver wages climbing, even as freight rates remain weak. ATA data shows that operational costs have risen by 25% more than revenue per mile — excluding fuel surcharges.

“This is why it’s been so tough…the cumulative effect of this is huge, and [it is] something some of these smaller fleets cannot get out of,” Costello said.

The used truck market has also been a major factor.

In 2022, used truck prices surged, making it difficult for fleets to upgrade equipment. Prices have since dropped, but if tariffs are introduced, used truck costs could spike again, making it harder to replace aging vehicles.

“Capacity has been leaving the industry. [Fleets] did not feel it because demand wasn’t really good,” he said, adding that since December 2022, more than 39,000 carriers, or 10.6% of the market, have exited the industry.

Another issue adding pressure to the market in U.S. is known as cabotage, Mexican B-1 visa drivers illegally hauling domestic U.S. freight.

“It’s absolutely happening, and it’s happening a lot,” Costello said, citing a response from border officials. He explained that some drivers are coerced into parking their trucks after crossing into the U.S. and take assignments in fleet-owned trucks for domestic hauls — allowing companies to pay them lower wages than American drivers.

Costello said that while the Biden administration has taken steps to address the issue, the new Trump administration would likely double down enforcement efforts, except they won’t just come after drivers alone, but after the fleets, too. “They’re going to go after the fleets. They can issue big fines. There have been people in the past that have gone to jail for this,” he said.

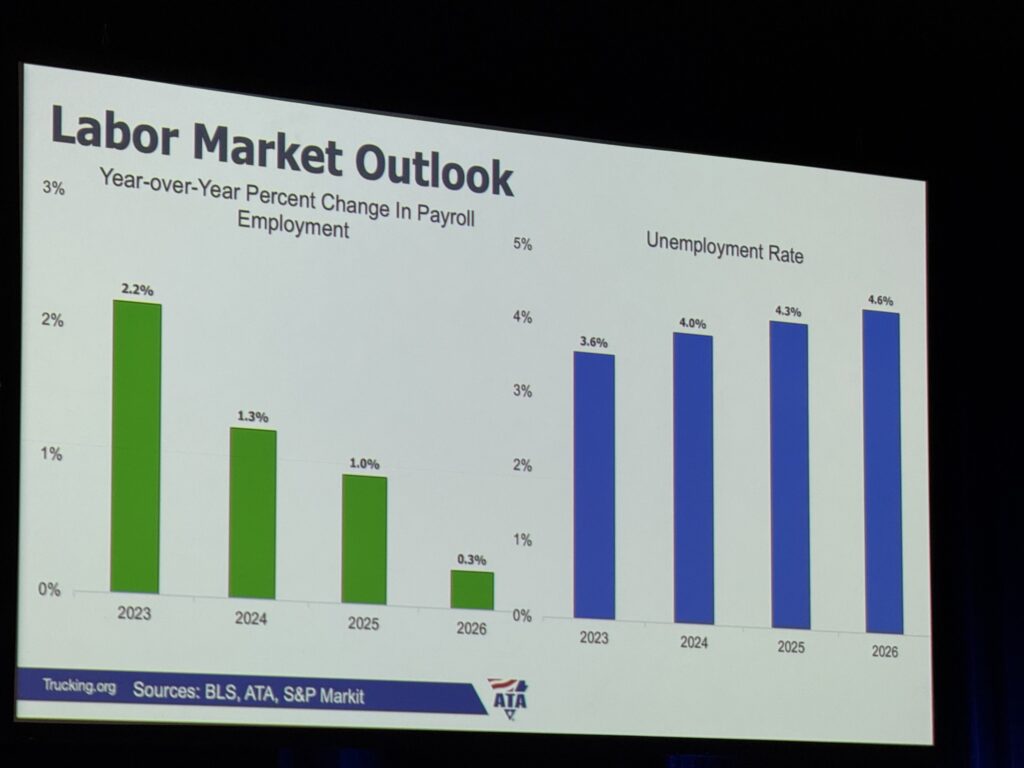

When speaking on the current administration’s immigration policies, he added that a cabotage crackdown and mass deportation might lead to a workforce shortage, further forcing fleets to raise wages for drivers and other staff.