Using this AI-powered app is simple: focus on one goal—operate to build a strong positive PES status. The reward is bigger profits.

UNDERSTANDING DASHBOARD PERFORMANCE INDICATORS LISTED BELOW - (CLICK HERE)

- ANNUAL PES: Tracks overall yearly profitability.

- MONTHLY PES: Monitors profit direction for the current month and resets monthly.

- RECOMMENDED (R)RATE: Shows minimum expected earnings for mileage.

- FUEL USAGE L/G: Indicates if fuel is being used efficiently (Gain) or inefficiently (Loss).

- Positive PES:

You're turning your gross revenue into higher net profits (more take-home cash).

This is how you keep succeeding in the trucking industry again and again. - Negative PES:

You're building up losses that can wipe out all your revenue and end up costing you money out of your own pocket.

If you're negative, it will appear in parentheses; for example, ($500)

Every day, take a moment to review your loads below to see which ones helped you earn more in profits and which ones caused a loss.

OPEN / CLOSE - (CLICK HERE)

TURN YOUR TRUCKING OPERATION INTO A POWERFUL PROFIT-MAKING SYSTEM - REGARDLESS OF MARKET CONDITIONS

* PES is the key to steady profit in any market. Every time the truck moves, the truck’s odometer changes—and so does your unique PES status.

* PES is the key to steady profit in any market. Every time the truck moves, the truck’s odometer changes—and so does your unique PES status.

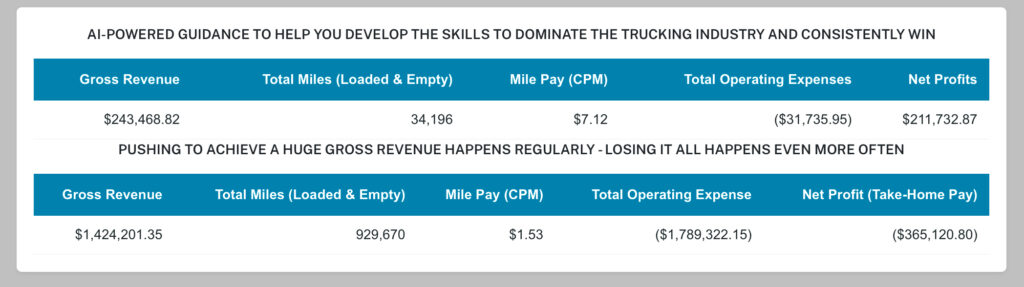

THE PROBLEM IS THE CONSISTENT ACCUMULATION OF MASSIVE LOSSES

Tested and Proven to Earning over $60,000 for every 10,000 total operated miles

A strong positive PES is how our clients have been consistently achieve over $60k+ for just 10,000 total (loaded + empty) miles, regardless of market conditions. This AI-powered self-training systems have been tested and proven for 11+ years to fit—and fix—any operation.SOME OF THE LOAD BOARDS WE USE - (CLICK HERE)

- DAT

- Internet TruckStop

- Uber Freight

- JB Hunt

- Ryans

- LandStar

- Flexport

- These are just a few, there are many more to help you keep your PES strong.

CONSISTENTLY BUILDING PROFITS

- UNIQUELY - IN ANY MARKET

Settings