Broker transparency and the enforcement of 49 CFR 371.3, pertaining to records to be kept by brokers and carriers’ right to review the record, remain among the hottest debates in trucking, with small carriers and owner-operators demanding visibility from brokers, and big brokers who would rather keep their cards close to their chest.

Earlier this year, Overdrive surveying, detailed in this report, found about 3 in 4 owner-operators want brokers to reveal the rates shippers pay, as required in the regulation. When Overdrive has published shipper-broker contracts in the past, readers showed plenty of interest — for instance, the Ikea contract with the original Convoy broker before it collapsed last Fall.

Much to the dismay of these owner-operators, 371.3 is one of those regulations that exists on paper but is seldom enforced, joining the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s stubborn refusal to assess fines for so-called “commercial” violations or potential acts of perjury against bad actors registered with the agency. As with those rules, the broker record-keeping regulation represents a rare case where small business trucking actually wants more enforcement. Unfortunately, despite promised action on petitions that might increase freight-transaction transparency, last year FMCSA kicked the can down the road. Trucking interests await news on the petitions that, if granted, could make the records disclosure automatic — the news could come as early as October this year.

[Related: ‘Continued delay is BS’: OOIDA on FMCSA’s move of broker transparency action to late 2024]

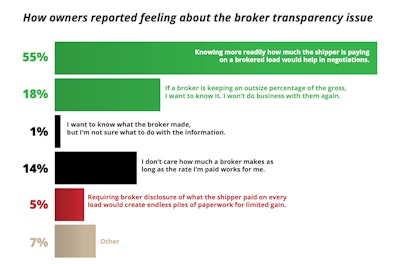

This chart, showing Overdrive owner-operator survey results around brokered-freight margins and transparency, was featured in a special report early in 2024. Download “Broker margins and spot rates reporting” perspectives via this link.

This chart, showing Overdrive owner-operator survey results around brokered-freight margins and transparency, was featured in a special report early in 2024. Download “Broker margins and spot rates reporting” perspectives via this link.

But brokers, and some of the 25% of Overdrive readers who fundamentally don’t care much about a broker’s rates with its shippers, offer a warning: Be careful what you wish for.

Deregulation’s ‘big bang’ changed everything: The crux of anti-transparency arguments

Overdrive spoke to Jeffrey Tucker, CEO of broker Tucker Company Worldwide and past chairman of the Transportation Intermediaries Association. Tucker’s a third-generation broker whose family history in trucking predates deregulation.

Tucker dove into his history to explore why broker transparency isn’t enforced, and how in his view it made more sense coming out of deregulation, which he compared to a “big bang” moment.

“In the days before 1980, trucking was basically monopolistic or oligopolistic,” said Tucker. “It was extremely regulated, and I’m not talking about safety. I’m talking about who can I contract with and where can I do business — that was regulated by the government.”

That’s when the “big bang” happened — deregulation stumbled out of the Carter administration and into Reagan’s in the 1980s. It marked the beginning of the end for the Interstate Commerce Commission, trucking’s commercial regulator at the time.

[Related: From wildcatting to deregulation, a ‘Brief history of trucking in America’]

Coming out of deregulation, carriers and brokers could freely enter the market, as long as they went through the “formality” of getting sponsored by an established industry player, according to Tucker. Tucker Company itself sponsored “tens of thousands” of new carriers entering the business over the 1980s, he said.

“At the time a broker’s only source of money was to ally itself with a motor carrier and say, ‘I can bring you business, and I want a percentage of the invoice,'” said Tucker. Essentially, brokers coming out of deregulation were little more than today’s equivalent of a “1099 carrier sales rep. … It made perfect sense that there was some sort of regulation for parties to the transaction” to have visibility into the charges assessed. “When this 371.3 was imagined, it was imagined during a time of somebody [earning] a percent of the invoice, but in the first few years of deregulation that changed.”

For Tucker, that’s the vital point. Broker transparency, decades ago, meant ensuring brokers got their agreed-upon percentage of a given load they booked for a carrier. Now, according to Tucker, it serves no purpose because there’s no agreed-upon percentages.

“There’s no such thing as an entity that I pay based on a percentage-of-an-invoice contract with customers,” said Tucker.

Imagine Tucker lands a contract with a big shipper covering lots of loads and lanes over an annual period. In the contract between Ikea and Convoy, Ikea agreed to pay the broker just $2.59/mile for a 304-mile run between Lebec and West Sacramento, California. In the same contract, a 316-mile load from Bolingbrook, Illinois, to West Chester, Ohio, though, would pay $4.07/mile under the terms. Undoubtedly, Convoy would stand to make money on some loads and lanes, while possibly losing money on others to land the contract. If market pressure climbed from the signing of the contract to the execution of the load, and the broker could only raise rates to carriers to get the loads moved, the prospects of losing money would rise even more. If the reverse happened, the broker could move the loads cheaper, and cash in.

DAT Freight & Analytics’ analytics chief, Ken Adamo, regularly tracks broker margins with his “Big rips and fat lips” index, charting their ebb and flow over time. Adamo puts the average broker margin around 15%, similar to what major publicly traded brokerages tend to report.

Carriers in search of a correct margin, though, Tucker suggested, will be looking a long time. “There is no right percentage,” said Tucker. “That’s just nonsense.”

[Related: Big Rips, Fat Lips: Biggest broker margins, fails reported in March]

Small carriers, brokers could unite to compete against mega fleets

In Tucker’s experience, most carriers either agree to a price or don’t, and it’s extremely rare to have “broker transparency” requested in freight transactions. “I can tell you Tucker has been in business 63 years. One time, and one time only ever, did a carrier ask to see my rate,” he said. “And that was soon after I wrote an article for Journal of Commerce” discussing broker margins.

The right to review brokered transactions, he said, is a “little bit of a ridiculous regulation to have on the books.”

In business, generally you don’t have a right to see contracts you’re not a party to, he said. Terms of a year-long contract between a shipper and a broker, then, shouldn’t fall under the 371.3 disclosure requirements. (For clarity, 371.3 doesn’t require full contracts to be disclosed. Rather, the regulation requires “freight charges” paid by the shipper and “brokerage service” fees collected by the broker to be available for review by any party to the transaction, including carriers.)

Generally, FMCSA staff report getting few requests for broker transparency.

“Carriers never see what a shipper pays me,” said Tucker. “God forbid.”

[Related: FMCSA forces broker transparency from Uber Freight after double-brokering scam]

In short, Tucker says both the reality of enforcement and daily business make the broker transparency debate more about “clickbait,” and whipping up anti-broker sentiment among carrier organizations, than any real policy or debate.

Tucker and the Transportation Intermediaries Association, which promotes his view of the issue. essentially have a reg on the books that they don’t like and can’t be compelled to abide by. Owner-operators and truck drivers of all sorts can perhaps relate. There’s all manner of regs on the books drivers don’t like and would love to ignore. (Yet owners and drivers generally aren’t so lucky to freely do so.)

Yet TIA, in collaboration with the Owner-Operator Independent Driver’s Association and other trucking orgs, are currently pushing a piece of legislation that, as TIA VP of Government Affairs Chris Burroughs said, would “put FMCSA’s feet to the fire in enforcing the regs” on the books as it related to double brokering. That legislation explicitly enables FMCSA to issue $10,000 fines for commercial-regs violations and various forms of entity fraud.

[Related: New bill would let FMCSA fine double brokers $10,000, crack down on shady actors]

So enforce the regs on the books, just not 371.3?

Tucker admitted that transparency, as imagined by many, would yield frankly mountains of actionable business intelligence for carriers. The most common views in Overdrive‘s broker transparency survey were that owner-ops would like to see shippers’ rates to help in negotiations (55%) and/or to avoid overly greedy brokers (18%).

“You know what, if I’m playing poker against someone, I want to see their cards,” he said. “But I think that the thought process is short-sighted.”

Why short-sighted? First off, Tucker described a “race to the bottom” dynamic he predicted widespread transparency would bring.

“If the regulation on the books was changed to require every transaction to show the buy and the sell price on that load, what is going to happen is the shipper is going to analyze the data and say, ‘Hey, we need to get the margin down from 13%,’ for example, ‘down to 10%,'” he said. “So then the big brokers will have to get a lot more sophisticated, buy more cost-effectively — driving down the cost of freight” movement.

If shippers get price transparency and demand savings, “that’s going to give shippers a price target, and everyone in trucking is going to feel the pain all the way down. It would be extreme, unnecessary pressure being placed on an already-stressed system.”

So what does Tucker propose instead?

A kind of union between owner-operators and brokers against the mega carriers.

“If we got our heads out of the sand and stopped crying in our Wheaties,” he said, “we would notice every single time there’s a capacity crisis and rates go up, there’s irrational exuberance and drivers come into the marketplace in droves. Then, when shippers go to bid they say, ‘Gosh that was painful in that capacity crisis, let’s align ourselves with big asset-based carriers.'”

If brokers were smart, Tucker added, “we would recognize that and we would market to the shippers and say, ‘Wake up! If you don’t want to blow your budget every two years, then keep us involved.'”

In that way, the broker community still stands ready to act as the salesforce for small carriers and owner-operators, he said. “We shouldn’t be at cross purposes, we need each other. Brokers and small carriers are tied at the hip, our fortunes are tied at the hip.”

Shippers know they pay brokers and freight forwarders a margin for convenience, and it’s incumbent upon the small trucking community to play the long game and convince shippers not to turn to big asset-based carriers, he said.

[Related: Broker margins, rates data, transparency: What owner-operators really think]