Supply Chains in EU and Ukraine total changed after 27 months of war

Today geopolitics becomes the major challenge for supply chains. During last three years majority of logistics challenges were connected to military conflicts and political instability, including the war in Ukraine, Red Sea crisis, Israel-Hamas war, potential China-Taiwan crisis.

Houthi attacks on container vessels in the Red Sea disrupted navigation through Suez Canal. This route accounts for 10-15% of world trade. Ships have to reroute around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. This can add 10-15 days to a journey and increase fuel costs by 40%.

Israel-Hamas war severely affected the operations of major ports in MENA, such as Ashdod and Haifa in Israel, and Rafah and Gaza in the Palestinian territories. Potential China-Taiwan crisis poses threat to navigation through the Taiwan Strait. This route is important for global trade as almost half of the global container fleet pass through it.

The war in Ukraine also disrupted supply chains. In the beginning of the war Russian military forces blocked shipping in Black Sea. As a result, 100 ships could not leave Ukrainian seaports. Ukraine could not export 120 mln tons of goods by sea annually, as before the war.

Supply chain challenges caused by geopolitical and other reasons create additional problems for companies. For example, logistics costs and lead times increase. Companies face shortages of raw materials and even have to stop production. Producers constantly need to search for new main suppliers. As a result, companies have to rebuild their supply chains.

Full study about «Changing logistic routes for Ukraine, Poland and EU after two years of war» you can read by link.

Sanctions against Russia: changes in trade flows of crude oil, natural gas, coal

The EU sanctions rebuild supply chains of crude oil & oil products globally. European Commission banned the seaborne imports of crude oil from Russia on 5.12.2022. As a result, China and India became the main consumers of Russian crude oil: from 5 December 2022 until the end of April 2024 they have bought 48% and 35% of Russia’s crude oil exports respectively. At the same time, the US replaced Russia as Europe’s number one oil supplier. Also, the EU increased oil imports from Saudi Arabia, Norway, Brazil, Iraq, Angola.

The EU has granted an exemption for crude oil imports through the southern branch of Druzhba pipeline, so such supplies continue to Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. However, Poland and Germany stopped pipeline oil imports from Russia (official ban was introduced on 23.06.2023, but in fact supplies were idled earlier).

The EU introduced ban on imports of Russian oil products (5.02.2023). As a result, Turkey became the largest buyer of Russian oil products: this country has purchased 24% of Russia’s oil product exports from February 2023 till April 2024. Other major consumers are China (12%) and Brazil (10%).

While India became major supplier of oil products to the EU. In 2023 the European Union’s imports of refined oil products from India increased by 115% y-o-y. In 2023, 20 out of the 27 EU countries imported refined oil products from India.

The EU banned imports of Russian coal on 8.04.2022. As a result, USA became the most important coal supplier to the EU (27% of imports in the EU last year), while China became the largest consumer of Russian coal (45% of all Russia’s coal exports from 5 December 2022 until the end of April 2024).

Russian LNG continues to flow into the EU, mostly through ports in Spain, Belgium and France. In 2023, 13% of the EU’s LNG imports by volume were from Russia. In 2023, the United States was the largest LNG supplier to the EU, representing almost 50% of total LNG imports.

In 2023 natural gas pipeline supplies to the EU was 28.3 bln m3 (31.0% of total pipeline exports from Russia). EU remains the largest consumer of Russian pipeline gas, however, supplies to the EU decreased by 55.6% y-o-y. Gazprom has instead increased gas sales to China, whose pipeline gas imports from Russia rose to 22.7 bln m3 in 2023, nearly 1.5 times more than in 2022.

How Ukraine has resumed exports during the war

Before the war, 90% of Ukrainian agricultural exports were handled in Ukrainian Black Sea ports. Russian navy blocked Ukrainian ports. As a result, during first months of the war average monthly grain exports decreased by more than 80% compared to pre-war months. Russia, on the contrary, increased its agricultural exports. In particularly, in marketing year 2022/2023 Russia rose exports of wheat by 50%.

In July 2022, Ukraine signed so called “grain agreement” with UN and Tukiye. Russia signed a mirror agreement with the UN and Turkiye. This action allowed unblocking the export of grain and other food products from three Ukrainian ports: Odessa, Chornomorsk, Pivdennyi. In July 2023, Russia exited “grain agreement”. In August 2023, Ukraine announced temporary route for civilian vessels moving from Ukrainian Black Sea seaports.

“Temporary export corridor” became more successful than “grain agreement”:

- from August 2023 to March 2024 Ukraine exported 34 mln tons through “temporary export corridor”;

- during the year of the grain agreement (July 2022 – July 2023), Ukraine exported 33 million tons of agricultural products.

“Temporary export corridor” allowed export of iron & steel products from Ukrainian sea ports. It is important since before the war iron & steel sector exported more than 60% of products through seaports (45 mln tons). Almost all pig iron was exported from Ukraine by sea transport. Although “temporary export corridor” is not fully safe, it allowed Ukrainian exporters to be more resilient having more possibilities to continue supplies.

During the war Ukrainian exporters had also to redirect cargo flows to EU seaports, in particularly in Romania (Constanta), Bulgaria (Burgas), Poland (Gdynia, Gdansk, Szczecin, Swinoujscie), Croatia (Rijeka, Ploce), Germany (Hamburg, Bremerhaven, Bremen). As a result, average distance to dispatch port for Ukrainian exporters increased 5 times and shipping costs to port of destination raised 3-4 times in average.

in 2023 Ukrainian ports of Danube handled 29 million tons of cargo. This is 2 times more than in the previous year and 6 times more than by 2021. During the war Danube ports were forced to partially reorient their work to coastal navigation for offshore transshipment in the port of Constanta (Romania). After the beginning of the war, Constanta became one of the main ports for Ukrainian exports. Ukrainian goods arrive in Constanta by road, rail and barge from the Ukrainian Danube ports of Reni and Izmail.

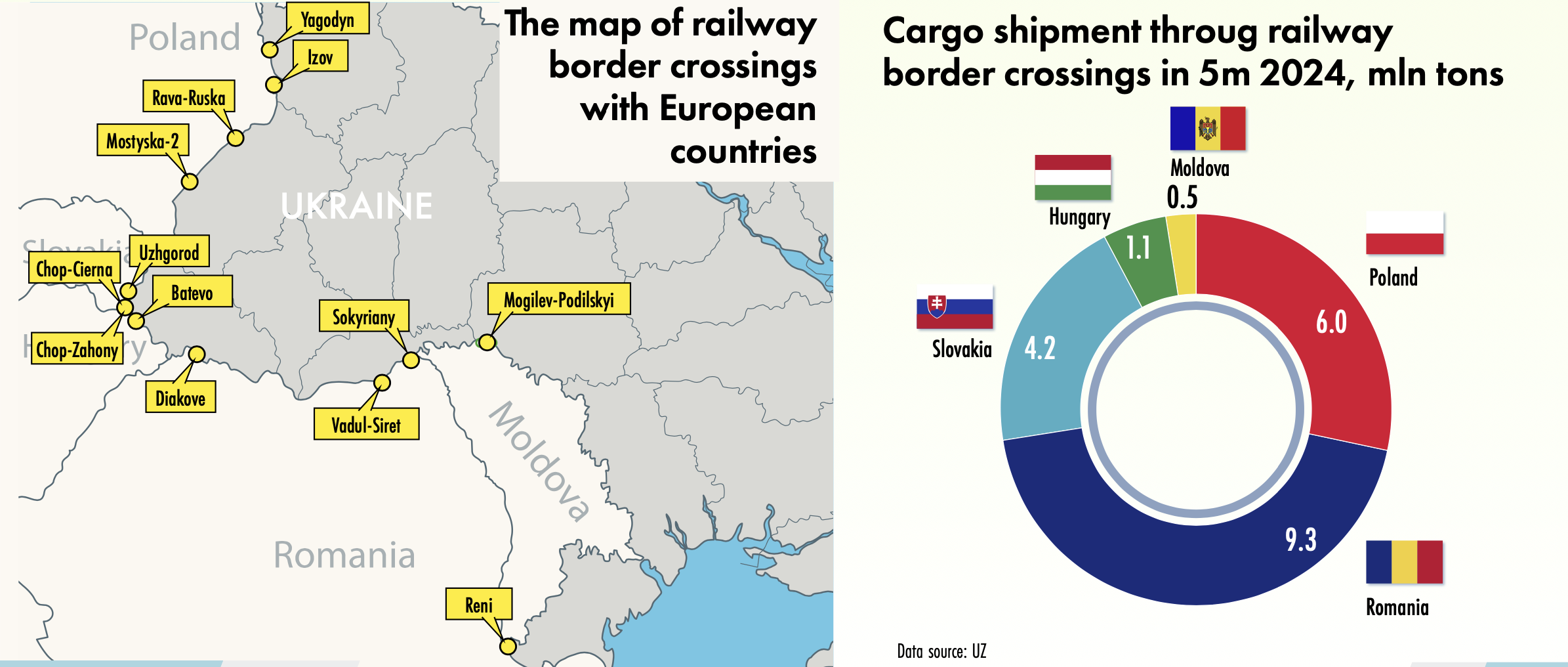

Poland and Romania became important transit destinations for Ukrainian exports. Through railway border crossings with these countries Ukraine exported more than 15 mln tons of cargo in 5 months 2024. Poland and Romania are transit hubs for Ukrainian products, that are sent to other European countries. Ukrainian business constructed hundred terminals, which work on both wide and European gauges. “Ukrzaliznytsia” allowed more than 30 private companies to develop border transshipment complexes.

Logistics flows changed in the EU and Ukraine as share of cars in deliveries increased. If in 2021 74% of passages through border crossings of Ukraine was made by car, last year this indicator reached almost 85%. Ukrainian companies increase usage of road transport as response to logistics constraints: blockade of seaports and limited capacity of railway crossings.

In June 2022 EU and Ukraine reached agreement on freight delivery by road transport. It cancelled the need for Ukrainian carriers to obtain appropriate permits for transportation to EU countries. Such agreement allowed to avoid stopping the export of Ukrainian products.

Poland – Ukraine collaboration in logistics

Polish railway became gate to the world for Ukrainian exporters after start of the war. In 2022, 16.9 mln tons of cargo were transported through railway border crossings between Ukraine and Poland. It is 36.7% more than in 2021. In January-April 2024, 7.4 mln tons of cargo were transported by rail to Poland. It is 28% more than in the same period in 2023. There are six railway border crossings between Ukraine and Poland, but only four are operational. They are utilized by 40-60%.

Several obstacles hinder high utilization of current capacities of railway border crossings between Ukraine and Poland. In particularly, there are more than 10 Polish carriers working at Yagodyn – Dorokhusk and Mostyska-2 – Medika checkpoints. The problem concerns prioritizing access to infrastructure to different Polish rail carriers.

Companies also tell about deficit of grain trucks, fitting platforms, Eurorail locomotives. Transshipment capacities at the border are not enough for Ukrainian export. Control procedures are duplicated since they are implemented by Polish and Ukrainian authorities. We observe absence of any advance scheduling for freight transportation through railway border crossings. So, it is not possible to predict speed of cargo movement.

Ukrainian exporters tried to ship cargo through Polish seaports, but they faced several problems: priority for own (Polish) cargo; lack of port capacity for transshipment (loading/unloading) of Ukrainian exports; lack of warehouse space for the accumulation of shipping lots. In general, capacities of Polish seaports are fully utilized, so there is no room for handling additional Ukrainian exports.

Car border crossings with Poland allowed Ukraine to satisfy humanitarian and military needs. Ukrainian trucks increased number of border passages by 34% in 2022 and 20% in 2023. Poland is a transit point for delivery to most countries in northern and western Europe. Transportations of fuel, humanitarian and military cargo take up about 20% of total traffic.

The blockade of the Polish border which began in November 2023 interrupted supply chains and led to losses. It is the first case of such interruption caused by political games. The blockade in various forms continued until the end of April 2024.

Direct consequences of the blockade included Increased logistic costs and prices and risen lead times. Trucking tariffs for delivery of steel finished products from Europe have increased 3-4 times. This increase in logistics costs added 10-15% to the price of imported steel. Trucks on average stood at the border for 12-14 days. It became not possible to deliver products from EU in 2-3 days. Ukrainian companies reported also about damage to business reputation, threats to food supply, price increases and reduced competitiveness.

Conclusions

The war created different challenges: blockade of Ukrainian seaports, shortage of freight transport, including trucks and railcars, shortage of car drivers, fuel deficit, overstocked warehouses, increased lead times, increased logistic costs, energy supply disruptions.

In general, Ukrainian companies adapted to war conditions. They redirected cargo to ports of other countries and diversify supply routes. They restructured fuel supply systems and increased use of road transport. Danube ports rose transshipment of cargo. Ukrainian supply chain managers constantly monitor new possibilities on cargo market and use every small possibility to ship cargo in any possible way. Implementation of European regulations to speed up procedures and integration into the EU supply chains is priority for Ukrainian companies.

Despite existing transportation options, free navigation through the Ukrainian Black Sea ports remains the basis for economy stability in Ukraine and the EU, as European logistics infrastructure cannot handle all Ukrainian exports due to several reasons: small size of seaports, different gauges of railway systems in Ukraine and the EU, deficit of railcars & locomotives in the EU, shortages of reloading capacities at the border crossings etc.